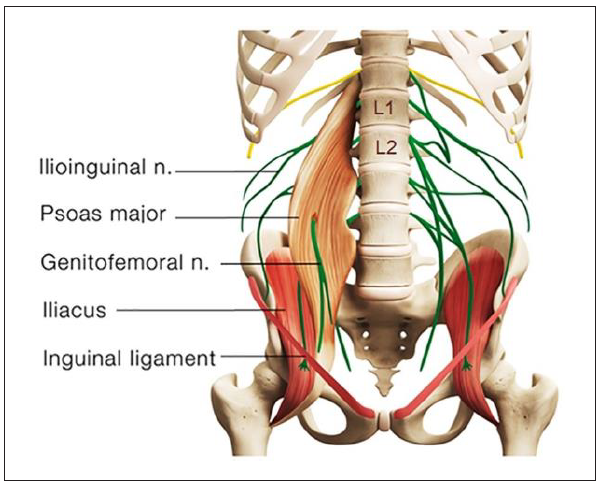

The testicles develop embryologically in the upper abdomen and descend into the scrotum shortly before birth. On their descent, the testes bring their sympathetic nerve supply with them from T10 to L1 segments and parasympathetic nerve supply from the S2 to S4 segments (Patel, 2017; Quallich & Arslanian-Engoren, 2013). The somatic supply to the testicles and scrotum originates from the L1–L2 and S2–S4 nerve roots through the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and pudendal nerves (Patel, 2017). The genitofemoral nerve, formed by a union of branches from the L1 and L2, splits into the genital and femoral branches after passing through the psoas muscle (Figure 2). The genital branch provides sensation to the cremaster muscle as well as the hemiscrotum in men and labia in women. The psoas major inserts on the lumbar discs, on the vertebral bodies, and on the transverse processes of the T12 to L5. As the psoas adheres to the lateral aspect of the fibrous annulus of the intervertebral discs, compression or inflammatory irritation derived from the lumbar discs can agitate the psoas muscle.

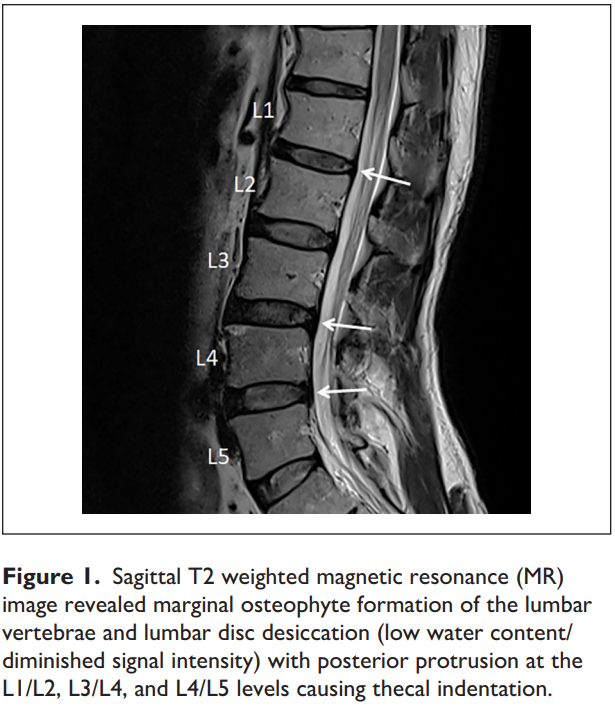

As shown in the present case, disc protrusion at the L1/L2, L3/L4, and L4/L5 levels was observed along with right psoas spasticity and right testicular pain. This patient had three potential pain sources. First, lumbar radiculopathy from encroachment or irritation of the L2 nerve root could radiate pain into the ipsilateral testicle (Patel, 2017). Second, discitis and/or facet arthrosis at other levels of the patient’s lumbar spine might also be capable of referring pain, transmitted nonsegmentally via the paravertebral sympathetic chain to the L1–L2 nerve Figure 1. Sagittal T2 weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image revealed marginal osteophyte formation of the lumbar vertebrae and lumbar disc desiccation (low water content/ diminished signal intensity) with posterior protrusion at the L1/L2, L3/L4, and L4/L5 levels causing thecal indentation. Chu 3 roots and in the genitofemoral nerve to the testicle (Doubleday et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2014). Third, the genitofemoral nerve penetrates the psoas muscle before splitting into the genital and femoral branches (Figure 2). Genitofemoral entrapment at the spastic psoas might also be involved in the advent of testicular pain (Masarani & Cox, 2003). Many of these hypotheses, as in this case, remain unconfirmed.

The pathophysiology of testicular pain is multifactorial and poorly understood. Diagnostic and treatment recommendations are based on expert opinion derived from small cohort studies (Patel, 2017). The appropriate approach to a patient presenting with CTP is to first rule out the possibility of serious pathology or red flag symptoms. When imaging is deemed necessary, a high-resolution scrotal ultrasound with color-flow Doppler is the primary modality used to detect and diagnose abnormalities within the scrotum. There can often be straightforward explanations for the CTP such as varicocele, infection, tumor, or referred pain from non-scrotal sources, but more often the etiology remains unexplained (Quallich & Arslanian-Engoren, 2013). Because of the overlapping sensory innervations and anatomic variability, it is difficult to differentiate the particular nerve involvement in cases of testicular pain.

The first step in the management of CTP with no red flag signs remains conservative in nature. Consideration should include the use of antibiotics, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications, pelvic floor physical therapy, or spermatic cord block. When conservative measures have failed, microsurgical testicular denervation and orchiectomy have been described as procedures of last resort. Unsuccessful recognition of the causative factors for CTP often leads to surgical failure, poor outcomes, and years of psychological distress (Doubleday et al., 2003). There is a scarcity of data on the association of CTP with degenerative lumbar spine disease. Case reports (Doubleday et al., 2003; Rowell & Rylander, 2012) revealed significant efficacy of manipulative therapies for alleviating testicular pain of spinal origin. According to the Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Lumbar Disc Herniation With Radiculopathy (Kreiner et al., 2014), spinal manipulation is an option for radiculopathy caused by discogenic disease. Remission of CTP observed in the present case appears to support that spinal manipulation could be a treatment regimen for testicular pain from this cause.

The exact mechanism underlying the action of chiropractic for the relief of discogenic pain remains unclear. Chiropractic trial in this case consisted of therapeutic ultrasound and spinal manipulation, along with intermittent motorized lumbar traction. Reported thermal effects of ultrasound upon tissue include raised tissue temperature, enhanced circulation, reduced muscle spasm, and increased extensibility of collagen fibers and a proinflammatory response (Speed, 2001). Biomechanical effects of chiropractic manipulation on symptom relief include relaxation of hypertonic musculature, release of entrapped nerves, disruption of periarticular adhesions, and restoration of spinal alignment (Onel et al., 1989). Lumbar traction is a form of decompression therapy, creating increased space and negative pressure of the intervertebral space. Intermittent mechanical traction can facilitate diffusion of nutrients for the disc and initiate the healing process. The main limitation of the present study is that the cause of testicular pain and mechanism of symptom relief are still uncertain without a control group. As a study retrospective in nature, the items regarding diagnosis, management, and outcome monitoring were not necessarily comprehensive. Larger scale studies regarding the efficacy of nonsurgical regimens for CTP are needed to provide corroboration.